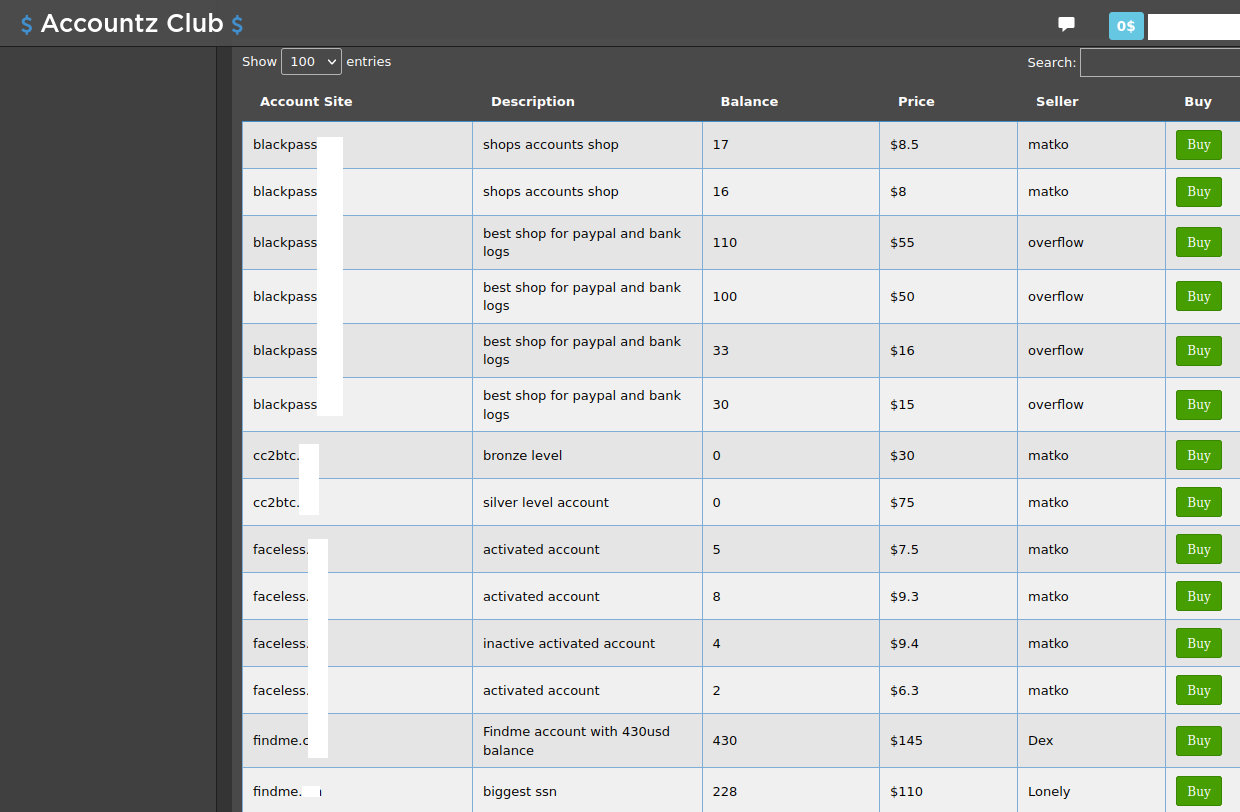

Up for the "Most Meta Cybercrime Offering" award this year is Accountz Club, a new cybercrime store that sells access to purloined accounts at services built for cybercriminals, including shops peddling stolen payment cards and identities, spamming tools, email and phone bombing services, and those selling authentication cookies for a slew of popular websites.

...moreSummary

Total Articles Found: 12

Top sources:

Top Keywords:

- A Little Sunshine: 4

- Ne'er-Do-Well News: 2

- Web Fraud 2.0: 1

- Accountz Club: 1

- Genesis Market: 1

Top Authors

- BrianKrebs: 4

Top Articles:

- How Not to Acknowledge a Data Breach

- Porn Clip Disrupts Virtual Court Hearing for Alleged Twitter Hacker

- DOGE to Fired CISA Staff: Email Us Your Personal Data

- Crime Shop Sells Hacked Logins to Other Crime Shops

- Hackers Were Inside Citrix for Five Months — Krebs on Security

- Lizard Kids: A Long Trail of Fail — Krebs on Security

- Source Code for IoT Botnet ‘Mirai’ Released — Krebs on Security

- Who is Anna-Senpai, the Mirai Worm Author? — Krebs on Security

- First ‘Jackpotting’ Attacks Hit U.S. ATMs — Krebs on Security

- Panerabread.com Leaks Millions of Customer Records — Krebs on Security

Crime Shop Sells Hacked Logins to Other Crime Shops

Published: 2022-01-21 17:11:36

Popularity: 40

Author: BrianKrebs

Keywords:

Porn Clip Disrupts Virtual Court Hearing for Alleged Twitter Hacker

Published: 2020-08-05 20:18:39

Popularity: 788

Author: BrianKrebs

Keywords:

Perhaps fittingly, a Web-streamed court hearing for the 17-year-old alleged mastermind of the July 15 mass hack against Twitter was cut short this morning after mischief makers injected a pornographic video clip into the proceeding.

...moreHackers Were Inside Citrix for Five Months — Krebs on Security

Published: 2020-02-19 20:22:24

Popularity: None

Author: None

🤖: "Citrix hack fest"

Networking software giant Citrix Systems says malicious hackers were inside its networks for five months between 2018 and 2019, making off with personal and financial data on company employees, contractors, interns, job candidates and their dependents. The disclosure comes almost a year after Citrix acknowledged that digital intruders had broken in by probing its employee accounts for weak passwords.

Citrix provides software used by hundreds of thousands of clients worldwide, including most of the Fortune 100 companies. It is perhaps best known for selling virtual private networking (VPN) software that lets users remotely access networks and computers over an encrypted connection.

In March 2019, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) alerted Citrix they had reason to believe cybercriminals had gained access to the company’s internal network. The FBI told Citrix the hackers likely got in using a technique called “password spraying,” a relatively crude but remarkably effective attack that attempts to access a large number of employee accounts (usernames/email addresses) using just a handful of common passwords.

In a statement released at the time, Citrix said it appeared hackers “may have accessed and downloaded business documents,” and that it was still working to identify what precisely was accessed or stolen.

But in a letter sent to affected individuals dated Feb. 10, 2020, Citrix disclosed additional details about the incident. According to the letter, the attackers “had intermittent access” to Citrix’s internal network between Oct. 13, 2018 and Mar. 8, 2019, and that there was no evidence that the cybercrooks still remain in the company’s systems.

Citrix said the information taken by the intruders may have included Social Security Numbers or other tax identification numbers, driver’s license numbers, passport numbers, financial account numbers, payment card numbers, and/or limited health claims information, such as health insurance participant identification number and/or claims information relating to date of service and provider name.

It is unclear how many people received this letter, but the communication suggests Citrix is contacting a broad range of individuals who work or worked for the company at some point, as well as those who applied for jobs or internships there and people who may have received health or other benefits from the company by virtue of having a family member employed by the company.

Citrix’s letter was prompted by laws in virtually all U.S. states that require companies to notify affected consumers of any incident that jeopardizes their personal and financial data. While the notification does not specify whether the attackers stole proprietary data about the company’s software and internal operations, the intruders certainly had ample opportunity to access at least some of that information as well.

Shortly after Citrix initially disclosed the intrusion in March 2019, a little-known security company Resecurity claimed it had evidence Iranian hackers were responsible, had been in Citrix’s network for years, and had offloaded terabytes of data. Resecurity also presented evidence that it notified Citrix of the breach as early as Dec. 28, 2018, a claim Citrix initially denied but later acknowledged.

Iranian hackers recently have been blamed for hacking VPN servers around the world in a bid to plant backdoors in large corporate networks. A report released this week (PDF) by security firm ClearSky details how Iran’s government-backed hacking units have been busy exploiting security holes in popular VPN products from Citrix and a number of other software firms.

ClearSky says the attackers have focused on attacking VPN tools because they provide a long-lasting foothold at the targeted organizations, and frequently open the door to breaching additional companies through supply-chain attacks. The company says such tactics have allowed the Iranian hackers to gain persistent access to the networks of companies across a broad range of sectors, including IT, security, telecommunications, oil and gas, aviation, and government.

Among the VPN flaws available to attackers is a recently-patched vulnerability (CVE-2019-19781) in Citrix VPN servers dubbed “Shitrix” by some in the security community. The derisive nickname may have been chosen because while Citrix initially warned customers about the vulnerability in mid-December 2019, it didn’t start releasing patches to plug the holes until late January 2020 — roughly two weeks after attackers started using publicly released exploit code to break into vulnerable organizations.

How would your organization hold up to a password spraying attack? As the Citrix hack shows, if you don’t know you should probably check, and then act on the results accordingly. It’s a fair bet the bad guys are going to find out even if you don’t.

Tags: Citrix Systems, CVE-2019-19781, fbi, Shitrix

This entry was posted on Wednesday, February 19th, 2020 at 10:55 am and is filed under A Little Sunshine, Data Breaches. You can follow any comments to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. You can skip to the end and leave a comment. Pinging is currently not allowed.

How Not to Acknowledge a Data Breach

Published: 2019-04-17 17:56:58

Popularity: 3576

Author: BrianKrebs

Keywords:

I'm not a huge fan of stories about stories, or those that explore the ins and outs of reporting a breach. But occasionally it seems necessary to publish such accounts when companies respond to a breach report in such a way that it's crystal clear that they wouldn't know what to do with a breach if it bit them in the nose, let alone festered unmolested in some dark corner of their operations.

...moreLizard Kids: A Long Trail of Fail — Krebs on Security

Published: 2019-03-08 00:28:29

Popularity: None

Author: None

🤖: "lizard people fail"

The Lizard Squad, a band of young hooligans that recently became Internet famous for launching crippling distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks against the largest online gaming networks, is now advertising its own Lizard-branded DDoS-for-hire service. Read on for a decidedly different take on this offering than what’s being portrayed in the mainstream media.

The new service, lizardstresser[dot]su, seems a natural evolution for a group of misguided youngsters that has sought to profit from its attention-seeking activities. The Lizard kids only ceased their attack against Sony’s Playstation and Microsoft’s Xbox Live networks last week after MegaUpload founder Kim Dotcom offered the group $300,000 worth of vouchers for his service in exchange for ending the assault. And in a development probably that shocks no one, the gang’s members cynically told Dailydot that both attacks were just elaborate commercials for and a run-up to this DDoS-for-hire offering.

The group is advertising the new “booter service” via its Twitter account, which has some 132,000+ followers. Subscriptions range from $5.99 per month for the ability to knock a target offline for 100 seconds at a time, to $129.99 monthly for DDoS attacks lasting more than eight hours.

In any case, I’m not terribly interested in turning this post into a commercial for the Lizard kids; rather, it’s a brain dump of related information I’ve gathered from various sources in the past 24 hours about the individuals and infrastructure that support the site.

In a show of just how little this group knows about actual hacking and coding, the source code for the service appears to have been lifted in its entirety from titaniumstresser, another, more established DDoS-for-hire booter service. In fact, these Lizard geniuses are so inexperienced at coding that they inadvertently exposed information about all of their 1,700+ registered users (more on this in a moment).

These two services, like most booters, are hidden behind CloudFlare, a content distribution service that lets sites obscure their true Internet address. In case anyone cares, Lizardstresser’s real Internet address currently is 217.71.50.57, at a hosting facility in Bosnia.

In any database of leaked forum or service usernames, it is usually safe to say that the usernames which show up first in the list are the administrators and/or creators of the site. The usernames exposed by the coding and authentication weaknesses in LizardStresser show that the first few registered users are “anti” and “antichrist.” As far as I can tell, these two users are the same guy: A ne’er-do-well who has previously sold access to his personal DDoS-for-hire service on Darkode — a notorious English-language cybercrime forum that I have profiled extensively on this blog.

As detailed in a recent, highly entertaining post on the blog Malwaretech, LizardSquad and Darkode are practically synonymous and indistinguishable now. Anyone curious about why the Lizard kids have picked on Yours Truly can probably find the answer in that Malwaretech story. As that post notes, the main online chat room for the Lizard kids (at lizardpatrol[dot]com) also is hidden behind CloudFlare, but careful research shows that it is actually hosted at the same Internet address as Darkode (5,38,89,132).

A suggested new banner for this blog from the jokers at black hat forum Darkode, which shares a server with the main chat forum for the Lizard kids.

In a show of just how desperate these kids are for attention, consider that the login page for LizardStresser currently says “Hosted somewhere on Brian Krebs’ forehead: Donate to the forehead reduction foundation, simply send money to krebsonsecurity@gmail.com on PayPal.” Many of you have done that in the past couple of days, although I doubt as a result of visiting the Lizard kids’ silly site. Anyway, for those generous donors, a hearty “thank you.”

It’s worth noting that the individual who registered LizardStresser is an interesting and angry teenager who appears to hail from Australia and uses the nickname “abdilo.” You can find his possibly not-safe-for-work rants on Twitter at this page. A reverse WHOIS lookup (ordered from Domaintools.com) on the email address used to register LizardStresser (9ajjs[at]zmail[dot]ru) shows this email has been used to register a number of domains tied to cybercrime operations, including sites selling stolen credit card data and access to hacked PCs.

A more nuanced lookup at Domaintools.com using some of this information turns up additional domains tied to Abdilo, including bkcn[dot]ru and abdilo[dot]ru (please do not attempt to visit these sites unless you know what you’re doing). Another domain that abdilo registered (in my name, no less) — http://x6b-x72-x65-x62-x73-x6f-x6e-x73-x65-x63-x75-x72-x69-x74-x79-x0[dot]com — is hexadecimal encoding for “krebsonsecurity.”

Last, but certainly not least, it appears that Vinnie Omari — the young man I identified earlier this week as being a self-proclaimed member of of the Lizard kids — has apparently just been arrested by the police in the United Kingdom (see screen shot below). Sources tell KrebsOnSecurity that Vinnie is one of many individuals associated with this sad little club who are being rounded up and questioned. My guess is most, if not all, of these kids will turn on one another. Time to go get some popcorn.

Happy New Year, everyone!

Tags: abdilo, booter service, CloudFlare, Darkode, Kim Dotcom, LizardSquad, lizardstresser, titaniumstresser, Vinnie Omari

This entry was posted on Wednesday, December 31st, 2014 at 1:24 pm and is filed under A Little Sunshine, Breadcrumbs, DDoS-for-Hire, The Coming Storm. You can follow any comments to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. Both comments and pings are currently closed.

Source Code for IoT Botnet ‘Mirai’ Released — Krebs on Security

Published: 2019-03-07 23:32:48

Popularity: None

Author: None

The source code that powers the “Internet of Things” (IoT) botnet responsible for launching the historically large distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attack against KrebsOnSecurity last month has been publicly released, virtually guaranteeing that the Internet will soon be flooded with attacks from many new botnets powered by insecure routers, IP cameras, digital video recorders and other easily hackable devices.

The leak of the source code was announced Friday on the English-language hacking community Hackforums. The malware, dubbed “Mirai,” spreads to vulnerable devices by continuously scanning the Internet for IoT systems protected by factory default or hard-coded usernames and passwords.

The Hackforums post that includes links to the Mirai source code.

Vulnerable devices are then seeded with malicious software that turns them into “bots,” forcing them to report to a central control server that can be used as a staging ground for launching powerful DDoS attacks designed to knock Web sites offline.

The Hackforums user who released the code, using the nickname “Anna-senpai,” told forum members the source code was being released in response to increased scrutiny from the security industry.

“When I first go in DDoS industry, I wasn’t planning on staying in it long,” Anna-senpai wrote. “I made my money, there’s lots of eyes looking at IOT now, so it’s time to GTFO [link added]. So today, I have an amazing release for you. With Mirai, I usually pull max 380k bots from telnet alone. However, after the Kreb [sic] DDoS, ISPs been slowly shutting down and cleaning up their act. Today, max pull is about 300k bots, and dropping.”

Sources tell KrebsOnSecurity that Mirai is one of at least two malware families that are currently being used to quickly assemble very large IoT-based DDoS armies. The other dominant strain of IoT malware, dubbed “Bashlight,” functions similarly to Mirai in that it also infects systems via default usernames and passwords on IoT devices.

According to research from security firm Level3 Communications, the Bashlight botnet currently is responsible for enslaving nearly a million IoT devices and is in direct competition with botnets based on Mirai.

“Both [are] going after the same IoT device exposure and, in a lot of cases, the same devices,” said Dale Drew, Level3’s chief security officer.

Infected systems can be cleaned up by simply rebooting them — thus wiping the malicious code from memory. But experts say there is so much constant scanning going on for vulnerable systems that vulnerable IoT devices can be re-infected within minutes of a reboot. Only changing the default password protects them from rapidly being reinfected on reboot.

In the days since the record 620 Gbps DDoS on KrebsOnSecurity.com, this author has been able to confirm that the attack was launched by a Mirai botnet. As I wrote last month, preliminary analysis of the attack traffic suggested that perhaps the biggest chunk of the attack came in the form of traffic designed to look like it was generic routing encapsulation (GRE) data packets, a communication protocol used to establish a direct, point-to-point connection between network nodes. GRE lets two peers share data they wouldn’t be able to share over the public network itself.

One security expert who asked to remain anonymous said he examined the Mirai source code following its publication online and confirmed that it includes a section responsible for coordinating GRE attacks.

It’s an open question why anna-senpai released the source code for Mirai, but it’s unlikely to have been an altruistic gesture: Miscreants who develop malicious software often dump their source code publicly when law enforcement investigators and security firms start sniffing around a little too close to home. Publishing the code online for all to see and download ensures that the code’s original authors aren’t the only ones found possessing it if and when the authorities come knocking with search warrants.

My guess is that (if it’s not already happening) there will soon be many Internet users complaining to their ISPs about slow Internet speeds as a result of hacked IoT devices on their network hogging all the bandwidth. On the bright side, if that happens it may help to lessen the number of vulnerable systems.

On the not-so-cheerful side, there are plenty of new, default-insecure IoT devices being plugged into the Internet each day. Gartner Inc. forecasts that 6.4 billion connected things will be in use worldwide in 2016, up 30 percent from 2015, and will reach 20.8 billion by 2020. In 2016, 5.5 million new things will get connected each day, Gartner estimates.

For more on what we can and must do about the dawning IoT nightmare, see the second half of this week’s story, The Democratization of Censorship. In the meantime, this post from Sucuri Inc. points to some of the hardware makers whose default-insecure products are powering this IoT mess.

Tags: anna-senpai, bashlight, Dale Drew, DDoS, Gartner Inc., Hackforums, Level3 Communications, mirai

This entry was posted on Saturday, October 1st, 2016 at 1:32 pm and is filed under Other. You can follow any comments to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. Both comments and pings are currently closed.

Who is Anna-Senpai, the Mirai Worm Author? — Krebs on Security

Published: 2019-03-07 23:23:27

Popularity: None

Author: None

On September 22, 2016, this site was forced offline for nearly four days after it was hit with “Mirai,” a malware strain that enslaves poorly secured Internet of Things (IoT) devices like wireless routers and security cameras into a botnet for use in large cyberattacks. Roughly a week after that assault, the individual(s) who launched that attack — using the name “Anna-Senpai” — released the source code for Mirai, spawning dozens of copycat attack armies online.

After months of digging, KrebsOnSecurity is now confident to have uncovered Anna-Senpai’s real-life identity, and the identity of at least one co-conspirator who helped to write and modify the malware.

Before we go further, a few disclosures are probably in order. First, this is easily the longest story I’ve ever written on this blog. It’s lengthy because I wanted to walk readers through my process of discovery, which has taken months to unravel. The details help in understanding the financial motivations behind Mirai and the botnet wars that preceded it. Also, I realize there are a great many names to keep track of as you read this post, so I’ve included a glossary.

The story you’re reading now is the result of hundreds of hours of research. At times, I was desperately seeking the missing link between seemingly unrelated people and events; sometimes I was inundated with huge amounts of information — much of it intentionally false or misleading — and left to search for kernels of truth hidden among the dross. If you’ve ever wondered why it seems that so few Internet criminals are brought to justice, I can tell you that the sheer amount of persistence and investigative resources required to piece together who’s done what to whom (and why) in the online era is tremendous.

As noted in previous KrebsOnSecurity articles, botnets like Mirai are used to knock individuals, businesses, governmental agencies, and non-profits offline on a daily basis. These so-called “distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks are digital sieges in which an attacker causes thousands of hacked systems to hit a target with so much junk traffic that it falls over and remains unreachable by legitimate visitors. While DDoS attacks typically target a single Web site or Internet host, they often result in widespread collateral Internet disruption.

A great deal of DDoS activity on the Internet originates from so-called ‘booter/stresser’ services, which are essentially DDoS-for-hire services which allow even unsophisticated users to launch high-impact attacks. And as we will see, the incessant competition for profits in the blatantly illegal DDoS-for-hire industry can lead those involved down some very strange paths, indeed.

THE FIRST CLUES

The first clues to Anna-Senpai’s identity didn’t become clear until I understood that Mirai was just the latest incarnation of an IoT botnet family that has been in development and relatively broad use for nearly three years.

Earlier this summer, my site was hit with several huge attacks from a collection of hacked IoT systems compromised by a family of botnet code that served as a precursor to Mirai. The malware went by several names, including “Bashlite,” “Gafgyt,” “Qbot,” “Remaiten,” and “Torlus.”

All of these related IoT botnet varieties infect new systems in a fashion similar to other well-known Internet worms — propagating from one infected host to another. And like those earlier Internet worms, sometimes the Internet scanning these systems perform to identify other candidates for inclusion into the botnet is so aggressive that it constitutes an unintended DDoS on the very home routers, Web cameras and DVRs that the bot code is trying to subvert and recruit into the botnet. This kind of self-defeating behavior will be familiar to those who recall the original Morris Worm, NIMDA, CODE RED, Welchia, Blaster and SQL Slammer disruptions of yesteryear.

Infected IoT devices constantly scan the Web for other IoT things to compromise, wriggling into devices that are protected by little more than insecure factory-default settings and passwords. The infected devices are then forced to participate in DDoS attacks (ironically, many of the devices most commonly infected by Mirai and similar IoT worms are security cameras).

Mirai’s ancestors had so many names because each name corresponded to a variant that included new improvements over time. In 2014, a group of Internet hooligans operating under the banner “lelddos” very publicly used the code to launch large, sustained attacks that knocked many Web sites offline.

The most frequent target of the lelddos gang were Web servers used to host Minecraft, a wildly popular computer game sold by Microsoft that can be played from any device and on any Internet connection.

The object of Minecraft is to run around and build stuff, block by large pixelated block. That may sound simplistic and boring, but an impressive number of people positively adore this game – particularly pre-teen males. Microsoft has sold more than a 100 million copies of Minecraft, and at any given time there are over a million people playing it online. Players can build their own worlds, or visit a myriad other blocky realms by logging on to their favorite Minecraft server to play with friends.

Image: Minecraft.net

A large, successful Minecraft server with more than a thousand players logging on each day can easily earn the server’s owners upwards of $50,000 per month, mainly from players renting space on the server to build their Minecraft worlds, and purchasing in-game items and special abilities.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the top-earning Minecraft servers eventually attracted the attention of ne’er-do-wells and extortionists like the lelddos gang. Lelddos would launch a huge DDoS attack against a Minecraft server, knowing that the targeted Minecraft server owner was likely losing thousands of dollars for each day his gaming channel remained offline.

Adding urgency to the ordeal, many of the targeted server’s loyal customers would soon find other Minecraft servers to patronize if they could not get their Minecraft fix at the usual online spot.

Robert Coelho is vice president of ProxyPipe, Inc., a San Francisco company that specializes in protecting Minecraft servers from attacks.

“The Minecraft industry is so competitive,” Coelho said. “If you’re a player, and your favorite Minecraft server gets knocked offline, you can switch to another server. But for the server operators, it’s all about maximizing the number of players and running a large, powerful server. The more players you can hold on the server, the more money you make. But if you go down, you start to lose Minecraft players very fast — maybe for good.”

In June 2014, ProxyPipe was hit with a 300 gigabit per second DDoS attack launched by lelddos, which had a penchant for publicly taunting its victims on Twitter just as it began launching DDoS assaults at the taunted.

At the time, ProxyPipe was buying DDoS protection from Reston, Va. -based security giant Verisign. In a quarterly report published in 2014, Verisign called the attack the largest it had ever seen, although it didn’t name ProxyPipe in the report – referring to it only as a customer in the media and entertainment business.

Verisign said the 2014 attack was launched by a botnet of more than 100,000 servers running on SuperMicro IPMI boards. Days before the huge attack on ProxyPipe, a security researcher published information about a vulnerability in the SuperMicro devices that could allow them to be remotely hacked and commandeered for these sorts of attacks.

THE CENTRALITY OF PROTRAF

Coelho recalled that in mid-2015 his company’s Minecraft customers began coming under attack from a botnet made up of IoT devices infected with Qbot. He said the attacks were directly preceded by a threat made by a then-17-year-old Christopher “CJ” Sculti, Jr., the owner and sole employee of a competing DDoS protection company called Datawagon.

Datawagon also courted Minecraft servers as customers, and its servers were hosted on Internet space claimed by yet another Minecraft-focused DDoS protection provider — ProTraf Solutions.

Christopher “CJ” Sculti, Jr.

According to Coelho, ProTraf was trying to woo many of his biggest Minecraft server customers away from ProxyPipe. Coelho said in mid-2015, Sculti reached out to him on Skype and said he was getting ready to disable Coelho’s Skype account. At the time, an exploit for a software weakness in Skype was being traded online, and this exploit could be used to remotely and instantaneously disable any Skype account.

Sure enough, Coelho recalled, his Skype account and two others used by co-workers were shut off just minutes after that threat, effectively severing a main artery of support for ProxyPipe’s customers – many of whom were accustomed to communicating with ProxyPipe via Skype.

“CJ messaged me about five minutes before the DDoS started, saying he was going to disable my skype,” Coelho said. “The scary thing about when this happens is you don’t know if your Skype account has been hacked and under control of someone else or if it just got disabled.”

Once ProxyPipe’s Skype accounts were disabled, the company’s servers were hit with a massive, constantly changing DDoS attack that disrupted ProxyPipe’s service to its Minecraft server customers. Coelho said within a few days of the attack, many of ProxyPipe’s most lucrative Minecraft servers had moved over to servers protected by ProTraf Solutions.

“In 2015, the ProTraf guys hit us offline tons, so a lot of our customers moved over to them,” Coelho said. “We told our customers that we knew [ProTraf] were the ones doing it, but some of the customers didn’t care and moved over to ProTraf anyway because they were losing money from being down.”

I found Coelho’s story fascinating because it eerily echoed the events leading up to my Sept. 2016 record 620 Gbps attack. I, too, was contacted via Skype by Sculti — on two occasions. The first was on July 7, 2015, when Sculti reached out apropos of nothing to brag about scanning the Internet for IoT devices running default usernames and passwords, saying he had uploaded some kind of program to more than a quarter-million systems that his scans found.

Here’s a snippet of that conversation:

July 7, 2015:

21:37 CJ: http://krebsonsecurity.com/2015/06/crooks-use-hacked-routers-to-aid-cyberheists/

21:37 CJ: vulnerable routers are a HUGE issue

21:37 CJ: a few months ago

21:37 CJ: I scanned the internet with a few sets of defualt logins

21:37 CJ: for telnet

21:37 CJ: and I was able to upload and execute a binary

21:38 CJ: on 250k devices

21:38 CJ: most of which were routers

21:38 Brian Krebs: o_0

The second time I heard from Sculti on Skype was Sept. 20, 2016 — the day of my 620 Gbps attack. Sculti was angry over a story I’d just published that mentioned his name, and he began rather saltily maligning the reputation of a source and friend who had helped me with that story.

Indignant on behalf of my source and annoyed at Sculti’s rant, I simply blocked his Skype account from communicating with mine and went on with my day. Just minutes after that conversation, however, my Skype account was flooded with thousands of contact requests from compromised or junk Skype accounts, making it virtually impossible to use the software for making phone calls or instant messaging.

Six hours after that Sept. 20 conversation with Sculti, the huge 620 Gbps DDoS attack commenced on this site.

WHO IS LELDDOS?

Coelho said he believes the main members of lelddos gang were Sculti and the owners of ProTraf. Asked why he was so sure of this, he recounted a large lelddos attack in early 2015 against ProxyPipe that coincided with a scam in which large tracts of Internet address space were temporarily stolen from the company.

According to ProxyPipe, a swath of Internet addresses was hijacked from the company by FastReturn, a cloud hosting firm. Dyn, a company that closely tracks which blocks of Internet addresses are assigned to which organizations, confirmed the timing of the Internet address hijack that Coelho described.

A few months after that attack, the owner of FastReturn — a young man named Ammar Zuberi — went to work as a software developer for ProTraf. In the process, Zuberi transferred the majority of Internet addresses assigned to FastReturn over to ProTraf.

Zuberi told KrebsOnSecurity that he was not involved with lelddos, but he acknowledged that he did hijack ProxyPipe’s Internet address space before moving over to ProTraf.

“I was stupid and new to this entire thing and it was interesting to me how insecure the underlying ecosystem of the Internet was,” Zuberi said. “I just kept pushing the envelope to see how far I could get with that, I guess. I eventually realized though and got away from it, although that’s not really much of a justification.”

According to Zuberi, CJ Sculti Jr. was a member of lelddos, as were the two co-owners of ProTraf. This is interesting because not long after the September 2016 Mirai attack took this site offline, several sources who specialize in lurking on cybercrime forums shared information suggesting that the principal author of Bashlite/Qbot was a ProTraf employee: A 19-year-old computer whiz from Washington, Penn. named Josiah White.

White’s profile on LinkedIn lists him as an “enterprise DDoS mitigation expert” at ProTraf, but for years he was better known to those in the hacker community under the alias “LiteSpeed.”

LiteSpeed is the screen name White used on Hackforums[dot]net – a sprawling English-language marketplace where mostly young, low-skilled hackers can buy and sell cybercrime tools and stolen goods with ease. Until very recently, Hackforums also was the definitive place to buy and sell DDoS-for-hire services.

I contacted White to find out if the rumors about his authorship of Qbot/Bashlite were true. White acknowledged that he had written some of Qbot/Bashlite’s components — including the code segment that the malware uses to spread the infection to new machines. But White said he never intended for his code to be sold and traded online.

White claims that a onetime friend and Hackforums member nicknamed “Vyp0r” betrayed his trust and forced him to publish the code online by threatening to post White’s personal details online and to “swat” his home. Swatting is a potentially deadly hoax in which an attacker calls in a fake hostage situation or bomb threat at a residence or business with the intention of sending a team of heavily-armed police officers to the target’s address.

“Most of the stuff that I had wrote was for friends, but as I later realized, things on HF [Hackforums] tend to not remain private,” White wrote in an instant message to KrebsOnSecurity. “Eventually I learned they were reselling them in under-the-table deals, and so I just released everything to stop that. I made some mistakes when I was younger, and I realize that, but I’m trying to set my path straight and move on.”

WHO IS PARAS JHA?

White’s employer ProTraf Solutions has only one other employee – 20-year-old President Paras Jha, from Fanwood, NJ. On his LinkedIn profile, Jha states that “Paras is a passionate entrepreneur driven by the want to create.” The profile continues:

“Highly self-motivated, in 7th grade he began to teach himself to program in a variety of languages. Today, his skillset for software development includes C#, Java, Golang, C, C++, PHP, x86 ASM, not to mention web ‘browser languages’ such as Javascript and HTML/CSS.”

Jha’s LinkedIn page also shows that he has extensive experience running Minecraft servers, and that for several years he worked for Minetime, one of the most popular Minecraft servers at the time.

After first reading Jha’s LinkedIn resume, I was haunted by the nagging feeling that I’d seen this rather unique combination of computer language skills somewhere else online. Then it dawned on me: The mix of programming skills that Jha listed in his LinkedIn profile is remarkably similar to the skills listed on Hackforums by none other than Mirai’s author — Anna-Senpai.

Prior to leaking the Mirai source code on HackForums at the end of September 2016, the majority of Anna-Senpai’s posts on Hackforums were meant to taunt other hackers on the forum who were using Qbot to build DDoS attack armies.

The best example of this is a thread posted to Hackforums on July 10, 2016 titled “Killing All Telnets,” in which Anna-Senpai boldly warns forum members that the malicious code powering his botnet contains a particularly effective “bot killer” designed to remove Qbot from infected IoT devices and to prevent systems infected with his malware from ever being reinfected with Qbot again.

Anna-Senpai warns Qbot users that his new worm (relatively unknown by its name “Mirai” at the time) was capable of killing off IoT devices infected with Qbot.

Initially, forum members dismissed Anna’s threats as idle taunts, but as the thread continues for page after page we can see from other forum members that his bot killer is indeed having its intended effect. [Oddly enough, it’s very common for the authors of botnet code to include patching routines to protect their newly-enslaved bots from being compromised by other miscreants. Just like in any other market, there is a high degree of competition between cybercrooks who are constantly seeking to add more zombies to their DDoS armies, and they often resort to unorthodox tactics to knock out the competition. As we’ll see, this kind of internecine warfare is a major element in this story.]

“When the owner of this botnet wrote a July 2016 Hackforums thread named ‘Killing all Telnets’, he was right,” wrote Allison Nixon and Pierre Lamy, threat researchers for New York City-based security firm Flashpoint. “Our intelligence around that time reflected a massive shift away from the traditional gafgyt infection patterns and towards a different pattern that refused to properly execute on analysts’ machines. This new species choked out all the others.”

It wasn’t until after I’d spoken with Jha’s business partner Josiah White that I began re-reading every one of Anna-Senpai’s several dozen posts to Hackforums. The one that made Jha’s programming skills seem familiar came on July 12, 2016 — a week after posting his “Killing All Telnets” discussion thread — when Anna-Senpai contributed to a Hackforums thread started by a hacker group calling itself “Nightmare.”

Such groups or hacker cliques are common on Hackforums, and forum members can apply for membership by stating their skills and answering a few questions. Anna-Senpai posted his application for membership into this thread among dozens of others, describing himself thusly:

“Age: 18+

Location and Languages Spoken: English

Which of the aforementioned categories describe you the best?: Programmer / Development

What do you Specialize in? (List only): Systems programming / general low level languages (C + ASM)

Why should we choose you over other applicants?: I have 8 years of development under my belt, and I’m very familiar with programming in a variety of languages, including ASM, C, Go, Java, C#, and PHP. I like to use this knowledge for personal gain.”

The Hackforums post shows Jha and Anna-Senpai have the exact same programming skills. Additionally, according to an analysis of Mirai by security firm Incapsula, the malicious software used to control a botnet powered by Mirai is coded in Go (a.k.a. “Golang”), a somewhat esoteric programming language developed by Google in 2007 that saw a surge in popularity in 2016. Incapsula also said the malcode that gets installed on IoT bots is coded in C.

DREADIS[NOT]COOL

I began to dig deeper into Paras Jha’s history and footprint online, and discovered that his father in October 2013 registered a vanity domain for his son, parasjha.info. That site is no longer online, but a historic version of it cached by the indispensable Internet Archive includes a resume of Jha’s early work with various popular Minecraft servers. Here’s a autobiographical snippet from parasjha.info:

“My passion is to utilize my skills in programming and drawing to develop entertaining games and software for the online game ‘Minecraft. Someday, I plan to start my own enterprise focused on the gaming industry targeted towards game consoles and the mobile platform. To further my ideas and help the gaming community, I have released some of my code to open source projects on websites centered on public coding under the handle dreadiscool.”

A Google search for this rather unique username “dreadiscool” turns up accounts by the same name at dozens of forums dedicated to computer programming and Minecraft. In many of those accounts, the owner is clearly frustrated by incessant DDoS attacks targeting his Minecraft servers, and appears eager for advice on how best to counter the assaults.

From Dreadiscool’s various online postings, it seems clear that at some point Jha decided it might be more profitable and less frustrating to defend Minecraft servers from DDoS attacks, as opposed to trying to maintain the servers themselves.

“My experience in dealing with DDoS attacks led me to start a server hosting company focused on providing solutions to clients to mitigate such attacks,” Jha wrote on his vanity site.

Some of the more recent Dreadiscool posts date to November 2016, and many of those posts are lengthy explanations of highly technical subjects. The tone of voice in these posts is far more confident and even condescending than the Dreadiscool from years earlier, covering a range of subjects from programming to DDoS attacks.

Dreadiscool’s account on Spigot Minecraft forum since 2013 includes some interesting characters photoshopped into this image.

For example, Dreadiscool has been an active member of the Minecraft forum spigotmc.org since 2013. This user’s avatar (pictured above) on spigotmc.org is an altered image taken from the 1994 Quentin Tarantino cult hit “Pulp Fiction,” specifically from a scene in which the gangster characters Jules and Vincent are pointing their pistols in the same direction. However, the heads of both actors have been digitally altered to include someone else’s faces.

Pasted over the head of John Travolta’s character (left) is a real-life picture of Vyp0r — the Hackforums nickname of the guy that ProTraf’s Josiah White said threatened him into releasing the source code for Bashlite. On the shoulders of Samuel L. Jackson’s body is the face of Tucker Preston, co-founder of BackConnect Security — a competing DDoS mitigation provider that also has a history of hijacking Internet address ranges from other providers.

Pictured below and to the left of Travolta and Jackson’s characters — seated on the bed behind them — is “Yamada,” a Japanese animation (“anime”) character featured in the anime movie B Gata H Hei.

Turns out, there is a Dreadiscool user on MyAnimeList.net, a site where members proudly list the various anime films they have watched. Dreadiscool says B Gata H Kei is one of nine anime film series he has watched. Among the other eight? The anime series Mirai Nikki, from which the Mirai malware derives its name.

Dreadiscool’s Reddit profile also is very interesting, and most of the recent posts there relate to major DDoS attacks going on at the time, including a series of DDoS attacks on Rutgers University. More on Rutgers later.

A CHAT WITH ANNA-SENPAI

At around the same time as the record 620 Gbps attack on KrebsOnSecurity, French Web hosting giant OVH suffered an even larger attack — launched by the very same Mirai botnet used to attack this site. Although this fact has been widely reported in the news media, the reason for the OVH attack may not be so well known.

According to a tweet from OVH founder and chief technology officer Octave Klaba, the target of that massive attack also was a Minecraft server (although Klaba mistakenly called the target “mindcraft servers” in his tweet).

A tweet from OVH founder and CTO, stating the intended target of Sept. 2016 Mirai DDoS on his company.

In the days following the attack on this site and on OVH, Anna-Sempai had trained his Mirai botnet on Coelho’s ProxyPipe, completely knocking his DDoS mitigation service offline for the better part of a day and causing problems for many popular Minecraft servers.

Unable to obtain more bandwidth and unwilling to sign an expensive annual contract with a third-party DDoS mitigation firm, Coelho turned to the only other option available to get out from under the attack: Filing abuse complaints with the Internet hosting firms that were responsible for providing connectivity to the control server used to orchestrate the activities of the Mirai botnet.

“We did it because we had no other options, and because all of our customers were offline,” Coelho said. “Even though no other DDoS mitigation company was able to defend against these attacks [from Mirai], we still needed to defend against it because our customers were starting to move to other providers that attracted fewer attacks.”

After scouring a list of Internet addresses tied to bots used in the attack, Coelho said he was able to trace the control server for the Mirai botnet back to a hosting provider in Ukraine. That company — BlazingFast[dot]io — has a reputation for hosting botnet control networks (even now, Spamhaus is reporting an IoT botnet controller running out of BlazingFast since Jan. 17, 2017).

Getting no love from BlazingFast, Coelho said he escalated his complaint to Voxility, a company that was providing DDoS protection to BlazingFast at the time.

“Voxility acknowledged the presence of the control server, and said they null-routed [removed] it, but they didn’t,” Coelho said. “They basically lied to us and didn’t reply to any other emails.”

Undeterred, Coelho said he then emailed the ISP that was upstream of BlazingFast, but received little help from that company or the next ISP further upstream. Coelho said the fifth ISP upstream of BlazingFast, however — Internet provider Telia Sonera — confirmed his report, and promptly had the Mirai botnet’s control server killed.

As a result, many of the systems infected with Mirai could no longer connect to the botnet’s control servers, drastically reducing the botnet’s overall firepower.

“The action by Telia cut the size of the attacks launched by the botnet down to 80 Gbps,” well within the range of ProxyPipe’s in-house DDoS mitigation capabilities, Coelho said.

Incredibly, on Sept. 28, Anna-Senpai himself would reach out to Coelho via Skype. Coelho shared a copy of that chat conversation with KrebsOnSecurity. The log shows that Anna correctly guessed ProxyPipe was responsible for the abuse complaints that kneecapped Mirai. Anna-Senpai said he guessed ProxyPipe was responsible after reading a comment on a KrebsOnSecurity blog post from a reader who shared the same username as Coelho’s business partner.

In the following chat, Coelho is using the Skype nickname “katie.onis.”

[10:23:08 AM] live:anna-senpai: ^

[10:26:08 AM] katie.onis: hi there.

[10:26:52 AM] katie.onis: How can I help you?

[10:28:06 AM] live:anna-senpai: hi

[10:28:45 AM] live:anna-senpai: you know i had my suspicions, but this one was proof

http://imgur.com/E1yFJOp [this is a benign/safe link to a screenshot of some comments on KrebsOnSecurity.com]

[10:28:59 AM] live:anna-senpai: don’t get me wrong, im not even mad, it was pretty funny actually. nobody has ever done that to my c2 [Mirai “command and control” server]

[10:29:25 AM] live:anna-senpai: (goldmedal)

[10:29:29 AM] katie.onis: ah you’re mistaken, that’s not us.

[10:29:33 AM] katie.onis: but we know who it is

[10:29:42 AM] live:anna-senpai: eric / 9gigs

[10:29:47 AM] katie.onis: no, 9gigs is erik

[10:29:48 AM] katie.onis: not eric

[10:29:53 AM] katie.onis: different people

[10:30:09 AM] live:anna-senpai: oh?

[10:30:17 AM] katie.onis: yep

[10:30:39 AM] live:anna-senpai: is he someone related to you guys?

[10:30:44 AM] katie.onis: not related to us, we just know him

[10:30:50 AM] katie.onis: anyway, we’re not interested in any harm, we simply don’t want attacks against us.

[10:31:16 AM] live:anna-senpai: yeah i figured, i added you because i wanted to tip my hat if that was actually you lol

[10:31:24 AM] katie.onis: we didn’t make that dumb post

[10:31:26 AM] katie.onis: if that is what you are asking

[10:31:30 AM] katie.onis: but yes, we were involved in doing that.

[10:31:47 AM] live:anna-senpai: so you got it nulled, but some other eric is claiming credit for it?

[10:31:52 AM] katie.onis: seems so.

[10:31:52 AM] live:anna-senpai: eric with a c

[10:31:56 AM] live:anna-senpai: lol

[10:32:17 AM] live:anna-senpai: can’t say im surprised, tons of people take credit for things that they didn’t do if nobody else takes credit for

[10:32:24 AM] katie.onis: we’re not interested in taking credit

[10:32:30 AM] katie.onis: we just wanted the attacks to get smaller

NOTICE AND TAKEDOWN

One reason Anna-Senpai may have been enamored of Coelho’s approach to taking down Mirai is that Anna-Senpai had spent the previous month doing exactly the same thing to criminals running IoT botnets powered by Mirai’s top rival — Qbot.

A month before this chat between Coelho and Anna-Senpai, Anna is busy sending abuse complaints to various hosting firms, warning them that they are hosting huge IoT botnet control channels that needed to be shut down. This was clearly just part of an extended campaign by the Mirai botmasters to eliminate other IoT-based DDoS botnets that might compete for the same pool of vulnerable IoT devices. Anna confirmed this in his chat with Coelho:

[10:50:36 AM] live:anna-senpai: i have good killer so nobody else can assemble a large net

[10:50:53 AM] live:anna-senpai: i monitor the devices to see for any new threats

[10:51:33 AM] live:anna-senpai: and when i find any new host, i get them taken down

The ISPs or hosting providers that received abuse complaints from Anna-Senpai were all encouraged to reply to the email address ogmemes123123@gmail.com for questions and/or confirmation of the takedown. ISPs that declined to act promptly on Anna-Senpai’s Qbot email complaints soon found themselves on the receiving end of enormous DDoS attacks from Mirai.

Francisco Dias, owner of hosting provider Frantech, found out firsthand what it would cost to ignore one of Anna’s abuse reports. In mid-September 2016, Francisco accidentally got into an Internet fight with Anna-Senpai. The Mirai botmaster was using the nickname “jorgemichaels” at the time — and Jorgemichaels was talking trash on LowEndTalk.com, a discussion forum for vendors of low-costing hosting.

Specifically, Jorgemichaels takes Francisco to task publicly on the forum for ignoring one of his Qbot abuse complaints. Francisco tells Jorgemichaels to file a complaint with the police if it’s so urgent. Jorgemichaels tells Francisco to shut up, and when Francisco is silent for a while Jorgemichaels gloats that Francisco learned his place. Francisco explains his further silence on the thread by saying he’s busy supporting customers, to which Jorgemichaels replies, “Sounds like you just got a lot more customers to help. Don’t mess with the underworld francisco or it will harm your business.”

Shortly thereafter, Frantech is systematically knocked offline after being attacked by Mirai. Below is a fascinating snippet from a private conversation between Francisco and Anna-Senpai/Jorgemichaels, in which Francisco kills the reported Qbot control server to make Anna/Jorgemichaels call off the attack.

Using the nickname “jorgemichaels” on LowEndTalk, Anna-Senpai reaches out to Francisco Dias after Dias ignores Anna’s abuse complaint. Francisco agrees to kill the Qbot control server only after being walloped with Mirai.

Back to the chat between Anna-Senpai and Coelho at the end of Sept 2016. Anna-Senpai tells Coelho that the attacks against ProxyPipe aren’t personal; they’re just business. Anna says he has been renting out “net spots” — sizable chunks of his Mirai botnet — to other hackers who use them in their own attacks for pre-arranged periods of time.

By way of example, Anna brags that as he and Coelho are speaking, the owners of a large Minecraft server were paying him to launch a crippling DDoS against Hypixel, currently the world’s most popular Minecraft server. KrebsOnSecurity confirmed with Hypixel that they were indeed under a massive attack from Mirai between Sept. 27 and 30.

[12:24:00 PM] live:anna-senpai: right now i just have a script sitting there hitting them for 45s every 20 minutes

[12:24:09 PM] live:anna-senpai: enough to drop all players and make them rage

Coelho told KrebsOnSecurity that the on-again, off-again attack DDoS method that Anna described using against Hypixel was designed not just to cost Hypixel money. The purpose of that attack method, he said, was to aggravate and annoy Hypixel’s customers so much that they might take their business to a competing Minecraft server.

“It’s not just about taking it down, it’s about making everyone who is playing on that server crazy mad,” Coelho explained. “If you launch the attack every 20 minutes for a short period of time, you basically give the players just enough time to get back on the server and involved in another game before they’re disconnected again.”

Anna-Senpai told Coelho that paying customers also were the reason for the 620 Gbps attack on KrebsOnSecurity. Two weeks prior to that attack, I published the results of a months-long investigation revealing that “vDOS” — one of the largest and longest-running DDoS-for-hire services — had been hacked, exposing details about the services owners and customers.

The story noted that vDOS earned its proprietors more than $600,000 and was being run by two 18-year-old Israeli men who went by the hacker aliases “applej4ck” and “p1st0”. Hours after that piece ran, Israeli authorities arrested both men, and vDOS — which had been in operation for four years — was shuttered for good.

[10:47:42 AM] live:anna-senpai: i sell net spots, starting at $5k a week

[10:47:50 AM] live:anna-senpai: and one client was upset about applejack arrest

[10:48:01 AM] live:anna-senpai: so while i was gone he was sitting on them for hours with gre and ack

[10:48:14 AM] live:anna-senpai: when i came back i was like oh fuck

[10:48:16 AM] live:anna-senpai: and whitelisted the prefix

[10:48:24 AM] live:anna-senpai: but then krebs tweeted that akamai is kicking them off

[10:48:31 AM] live:anna-senpai: fuck me

[10:48:43 AM] live:anna-senpai: he was a cool guy too, i like his article

[SIDE NOTE: If true, it’s ironic that someone would hire Anna-Senpai to attack my site in retribution for the vDOS story. That’s because the firepower behind applej4ck’s vDOS service was generated in large part by a botnet of IoT systems infected with a Qbot variant — the very same botnet strain that Anna-Senpai and Mirai were busy killing and erasing from the Internet.]

Coelho told KrebsOnSecurity that if his side of the conversation reads like he was being too conciliatory to his assailant, that’s because he was wary of giving Anna a reason to launch another monster attack against ProxyPipe. After all, Coelho said, the Mirai attacks on ProxyPipe caused many customers to switch to other Minecraft servers, and Coelho estimates the attack cost the company between $400,000 and $500,000.

Nevertheless, about halfway through the chat Coelho gently confronts Anna on the consequences of his actions.

[10:54:17 AM] katie.onis: People have a genuine reason to be unhappy though about large attacks like this

[10:54:27 AM] live:anna-senpai: yeah

[10:54:32 AM] katie.onis: There’s really nothing anyone can do lol

[10:54:36 AM] live:anna-senpai: 😛

[10:54:38 AM] katie.onis: And it does affect their lives

[10:55:10 AM] live:anna-senpai: well, i stopped caring about other people a long time ago

[10:55:18 AM] live:anna-senpai: my life experience has always been get fucked over or fuck someone else over

[10:55:52 AM] katie.onis: My experience with [ProxyPipe] thus far has been

[10:55:54 AM] katie.onis: Do nothing bad to anyone

[10:55:58 AM] katie.onis: And still get screwed over

[10:55:59 AM] katie.onis: Haha

The two even discussed anime after Anna-Senpai guessed that Coelho might be a fan of the genre. Anna-Senpai says he watched the anime series “Gate,” a reference to the above-mentioned B Gata H Hei that Dreadiscool included in the list of anime film series he’s watched. Anna also confirms that the name for his bot malware was derived from the anime series Mirai Nikki.

[5:25:12 PM] live:anna-senpai: i rewatched mirai nikki recently

[5:25:22 PM] live:anna-senpai: (it was the reason i named my bot mirai lol)

DREADISCOOL = ANNA = JHA?

Coelho said when Anna-Senpai first reached out to him on Skype, he had no clue about the hacker’s real-life identity. But a few weeks after that chat conversation with Anna-Senpai, Coelho’s business partner (the Eric referenced in the first chat segment above) said he noticed that some of the code in Mirai looked awfully similar to code that Dreadiscool had posted to his Github account.

“He started to come to the conclusion that maybe Anna was Paras,” Coelho said. “He gave me a lot of ideas, and after I did my own investigation I decided he was probably right.”

Coelho said he’s known Paras Jha for more than four years, having met him online when Jha was working for Minetime — which ProxyPipe was protecting from DDoS attacks at the time.

“We talked a lot back then and we used to program a lot of projects together,” Coelho said. “He’s really good at programming, but back then he wasn’t. He was a little bit behind, and I was teaching him most everything.”

According to Coelho, as Jha became more confident in his coding skills, he also grew more arrogant, belittling others online who didn’t have as firm a grasp on subjects such as programming and DDoS mitigation.

“He likes to be recognized for his knowledge, being praised and having other people recognize that,” Coelho said of Jha. “He brags too much, basically.”

Coelho said not long after Minetime was hit by a DDoS extortion attack in 2013, Paras joined Hackforums and fairly soon after stopped responding to his online messages.

“He just kind of dropped off the face of the earth entirely,” he said. “When he started going on Hackforums, I didn’t know him anymore. He became a different person.”

Coelho said he doesn’t believe his old friend wished him harm, and that Jha was probably pressured into attacking ProxyPipe.

“In my opinion he’s still a kid, in that he gets peer-pressured a lot,” Coelho said. “If he didn’t [launch the attack] not only would he feel super excluded, but these people wouldn’t be his friends anymore, they could out him and screw him over. I think he was pretty much in a really bad position with the people he got involved with.”

THE RUTGERS DDOS ATTACKS

On Dec. 16, security vendor Digital Shadows presented a Webinar that focused on clues about the Mirai author’s real life identity. According to their analysis, before the Mirai author was known as Anna-Senpai on Hackforums, he used the nickname “Ogmemes123123” (this also was the alias of the Skype username that contacted Coelho), and the email address ogmemes123123@gmail.com (recall this is the same email address Anna-Senpai used in his alerts to various hosting firms about the urgent need to take down Qbot control servers hosted on their networks).

Digital Shadows noted that the Mirai author appears to have used another nickname: “OG_Richard_Stallman,” a likely reference to the founder of the Free Software Foundation. The ogmemes123123@gmail.com account was used to register a Facebook account in the name of OG_Richard Stallman.

That Facebook account states that OG_Richard_Stallman began studying computer engineering at New Brunswick, NJ-based Rutgers University in 2015.

As it happens, Paras Jha is a student at Rutgers University. This is especially notable because Rutgers has been dealing with a series of DDoS attacks on its network since the fall semester of 2015 — more than a half dozen incidents in all. With each DDoS, the attacker would taunt the university in online posts and media interviews, encouraging the school to spend the money to purchase some kind of DDoS mitigation service.

Using the nicknames “og_richard_stallman,” “exfocus” and “ogexfocus,” the person who attacked Rutgers more than a half-dozen times took to Reddit and Twitter to claim credit for the attacks. Exfocus even created his own “Ask Me Anything” interview on Reddit to discuss the Rutgers attacks.

Exfocus also gave an interview to a New Jersey-based blogger, claiming he got paid $500 an hour to DDoS the university with as many as 170,000 bots. Here are a few snippets from that interview, in which he blames the attacks on a “client” who is renting his botnet:

“Are you for real? Why would you do an interview with us if you’re getting paid?

Normally I don’t show myself, but the entity paying me has something against the school. They want me to “make a splash”.

Why do you have a twitter account where you publically broadcast patronizing messages. Are you worried that this increases the risk of things getting back to you?

Public twitter is on clients request. The client hates the school for whatever reason. They told me to say generic things like that I hate the bus system and etc.

Have you ever attacked RU before?

During freshman registration the client requested it also – he didn’t want any publicity then though.

What are your plans for the future in terms of DDOSing and attacking the Rutgers cyber infrastructure?

When I stop getting paid – I’ll stop DDosing lol. I’m hoping that RU will sign on some ddos mitigation provider. I get paid extra if that happens.

At some point you said you were at the Livingston student center – outside of Sbarro. In this interview you said that you aren’t affiliated directly with Rutgers, did you lie then?

Yes”

An online search for the Gmail address used by Anna-Senpai and OG_Richard_Stallman turns up a Pastebin post from July 1, 2016, in which an anonymous Pastebin user creates a “dox” of OG_Richard_Stallman. Doxing refers to the act of publishing someone’s personal information online and/or connecting an online alias to a real life identity.

The dox said OG_Richard_Stallman was connected to an address and phone number of an individual living in Turkey. But this is almost certainly a fake dox intended to confuse cybercrime investigators. Here’s why:

A Google search shows that this same address and phone number showed up in another dox on Pastebin from almost three years earlier — June 2013 — intended to expose or confuse the identity of a Hackforums user known as LiteSpeed. Recall that LiteSpeed is the same alias that ProTraf’s Josiah White acknowledged using on Hackforums.

EXTORTION ATTEMPTS BY OG_RICHARD_STALLMAN

This OG_Richard_Stallman identity is connected to Anna-Senpai by another person we’ve heard from already: Francisco Dias, whose Frantech ISP was attacked by Anna-Senpai and Mirai in mid-September. Francisco told KrebsOnSecurity that in early August 2016 he began receiving extortion emails from a Gmail address associated with a OG_Richard_Stallman.

“This guy using the Richard Stallman name added me on Skype and basically said ‘I’m going to knock all of your [Internet addresses] offline until you pay me’,” Dias recalled. “He told me the up front cost to stop the attack was 10 bitcoins [~USD $5,000 at the time], and if I didn’t pay within four hours after the attack started the fee would double to 20 bitcoins.”

Dias said he didn’t pay the demand and eventually OG_Richard_Stallman called off the attack. But he said for a while the attacks were powerful enough to cause problems for Frantech’s Internet provider.

“He was hitting us so hard with Mirai that he was dropping large parts of Hurricane Electric and causing problems at their Los Angeles point of presence,” Dias said. “I basically threw everything behind [DDoS mitigation provider] Voxility, and eventually Stallman buggered off.”

The OG_Richard_Stallman identity also was tied to similar extortion attacks at the beginning of August against one hosting firm that had briefly been one of ProTraf’s customers in 2016. The company declined to be quoted on the record, but said it stopped doing business with Protraf in mid-2016 because they were unhappy with the quality of service.

The Internet provider said not long after that it received an extortion demand from the “OG_Richard_Stallman” character for $5,000 in Bitcoin to avoid a DDoS attack. One of the company’s researchers contacted the extortionist via the ogmemes123123@gmail.com address supplied in the email, but posing as someone who wished to hire some DDoS services.

OG_Richard_Stallman told the researcher that he could guarantee 350 Gbps of attack traffic and that the target would go down or the customer would receive a full refund. The price for the attack? USD $100 worth of Bitcoin for every five minutes of attack time.

My source at the hosting company said his employer declined to pay the demand, and subsequently got hit with an attack from Mirai that clocked in at more than 300 Gbps.

“Clearly, the attacker is very technical, as they attacked every single [Internet address] within the subnet, and after we brought up protection, he started attacking upstream router interfaces,” the source said on condition of anonymity.

Asked who they thought might be responsible for the attacks, my source said his employer immediately suspected ProTraf. That’s because the Mirai attack also targeted the Internet address for the company’s home page, but that Internet address was hidden by DDoS mitigation firm Cloudflare. However, ProTraf knew about the secret address from its previous work with the company, the source explained.

“We believe it’s Protraf’s staff or someone related to Protraf,” my source said.

A source at an Internet provider agreed to share information about an extortion demand his company received from OG_Richard_Stallman in August 2016. Here he is contacting the Stallman character directly and pretending to be someone interested in renting a botnet. Notice the source brazenly said he wanted to DDoS ProTraf.

DDOS CONFESSIONS

After months of gathering information about the apparent authors of Mirai, I heard from Ammar Zuberi, once a co-worker of ProTraf President Paras Jha.

Zuberi told KrebsOnSecurity that Jha admitted he was responsible for both Mirai and the Rutgers DDoS attacks. Zuberi said when he visited Jha at his Rutgers University dorm in October 2015, Paras bragged to him about launching the DDoS attacks against Rutgers.

“He was laughing and bragging about how he was going to get a security guy at the school fired, and how they raised school fees because of him,” Zuberi recalled. “He didn’t really say why he did it, but I think he was just sort of experimenting with how far he could go with these attacks.”

Zuberi said he didn’t realize how far Jha had gone with his DDoS attacks until he confronted him about it late last year. Zuberi said he was on his way to see his grandmother in Arizona at the end of November 2016, and he had a layover in New York. So he contacted Jha and arranged to spend the night at Jha’s home in Fanwood, New Jersey.

As I noted in Spreading the DDoS Disease and Selling the Cure, Anna-Senpai leaked the Mirai code on a domain name (santasbigcandycane[dot]cx) that was registered via Namecentral, an extremely obscure domain name registrar which had previously been used to register fewer than three dozen other domains over a three-year period.

According to Zuberi, only five people knew about the existence of Namecentral: himself, CJ Sculti, Paras Jha, Josiah White and Namecentral’s owner Jesse Wu (19-year-old Wu features prominently in the DDoS Disease story linked in the previous paragraph).

“When I saw that the Mirai code had been leaked on that domain at Namecentral, I straight up asked Paras at that point, ‘Was this you?,’ and he smiled and said yep,” Zuberi recalled. “Then he told me he’d recently heard from an FBI agent who was investigating Mirai, and he showed me some text messages between him and the agent. He was pretty proud of himself, and was bragging that he led the FBI on a wild goose chase.”

Zuberi said he hasn’t been in contact with Jha since visiting his home in November. Zuberi said he believes Jha wrote most of the code that Mirai uses to control the individual bot-infected IoT devices, since it was written in Golang and Jha’s partner White didn’t code well in this language. Zuberi said he thought White’s role was mainly in developing the spreading code used to infect new IoT devices with Mirai, since that was written in C — a language White excelled at.

In the time since most of the above occurred, the Internet address ranges previously occupied by ProTraf have been withdrawn. ProxyPipe’s Coelho said it could be that the ProTraf simply ran out of money.

ProTraf’s Josiah White explained the disappearance of ProTraf’s Internet space as part of an effort to reboot the company.

“We [are] in the process of restructuring and refocusing what we are doing,” White told KrebsOnSecurity.

Jha did not respond to requests for comment.

Update: Jan. 19, 10:51 a.m. ET: Jha responded to my request for comment. His first comment about this story was that I erred in citing the proper anime film listed on one of the dreadiscool profiles mentioned above. When asked directly about his alleged involvement with Mirai, Jha said he did not write Mirai and was not involved in attacking Rutgers.

“The first time it happened, I was a freshman, and living in the dorms,” Jha said. “At the culmination of the attacks near the end of the year, I was without internet for almost a week, along with the rest of the student body. I couldn’t register for classes, and had a host of issues dealing with it. This semester and the previous semester were the reasons I moved to commute, because of these problems that I frankly don’t have time to deal with.”

Jha said Zuberi did spend the night at his house last year but he denied admitting anything to Zuberi. He acknowledged hearing from an FBI agent investigating Mirai, but said “no comment” when asked if he’d heard from that FBI agent since then.

“I don’t think there are enough facts to definitively point the finger at me,” Jha said. “Besides this article, I was pretty much a nobody. No history of doing this kind of stuff, nothing that points to any kind of sociopathic behavior. Which is what the author is, a sociopath.”

Original story:

Rutgers University did not respond to requests for comment.

FBI officials could not be immediately reached for comment.

A copy of the entire chat between Anna-Senpai and ProxyPipe’s Coelho is available here.

Tags: Allison Nixon, Ammar Zuberi, anime, anna-senpai, applej4ck, BASHLITE, BlazingFast, bulletproof hoster, CJ Sculti, datawagon, DDoS, ddos-for-hire, dox, dreadiscool, exfocus, Fastreturn, Fracisco Dias, Frantech, Golang, Hackforums, Hypixel, Incapsula, Jesse Wu, Josiah White, lelddos, LiteSpeed, Minecraft, Minetime, Mirai Nikki, Namecentral, ogexfocus, ogmemes123123@gmail.com, OG_Richard_Stallman, p1st0, Paras Jha, Pierre Lamy, ProTraf, Protraf Solutions, ProxyPipe, Qbot, Richard Stallman, Robert Coelho, Rutgers University DDoS, Supermicro, SWATting, switchnet.io, vDos, Verisign, Vyp0r

This entry was posted on Wednesday, January 18th, 2017 at 12:48 pm and is filed under Other. You can follow any comments to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. Both comments and pings are currently closed.

First ‘Jackpotting’ Attacks Hit U.S. ATMs — Krebs on Security

Published: 2019-03-07 22:33:15

Popularity: None

Author: None

ATM “jackpotting” — a sophisticated crime in which thieves install malicious software and/or hardware at ATMs that forces the machines to spit out huge volumes of cash on demand — has long been a threat for banks in Europe and Asia, yet these attacks somehow have eluded U.S. ATM operators. But all that changed this week after the U.S. Secret Service quietly began warning financial institutions that jackpotting attacks have now been spotted targeting cash machines here in the United States.

To carry out a jackpotting attack, thieves first must gain physical access to the cash machine. From there they can use malware or specialized electronics — often a combination of both — to control the operations of the ATM.

A keyboard attached to the ATM port. Image: FireEye

On Jan. 21, 2018, KrebsOnSecurity began hearing rumblings about jackpotting attacks, also known as “logical attacks,” hitting U.S. ATM operators. I quickly reached out to ATM giant NCR Corp. to see if they’d heard anything. NCR said at the time it had received unconfirmed reports, but nothing solid yet.

On Jan. 26, NCR sent an advisory to its customers saying it had received reports from the Secret Service and other sources about jackpotting attacks against ATMs in the United States.

“While at present these appear focused on non-NCR ATMs, logical attacks are an industry-wide issue,” the NCR alert reads. “This represents the first confirmed cases of losses due to logical attacks in the US. This should be treated as a call to action to take appropriate steps to protect their ATMs against these forms of attack and mitigate any consequences.”

The NCR memo does not mention the type of jackpotting malware used against U.S. ATMs. But a source close to the matter said the Secret Service is warning that organized criminal gangs have been attacking stand-alone ATMs in the United States using “Ploutus.D,” an advanced strain of jackpotting malware first spotted in 2013.

According to that source — who asked to remain anonymous because he was not authorized to speak on the record — the Secret Service has received credible information that crooks are activating so-called “cash out crews” to attack front-loading ATMs manufactured by ATM vendor Diebold Nixdorf.

The source said the Secret Service is warning that thieves appear to be targeting Opteva 500 and 700 series Dielbold ATMs using the Ploutus.D malware in a series of coordinated attacks over the past 10 days, and that there is evidence that further attacks are being planned across the country.

“The targeted stand-alone ATMs are routinely located in pharmacies, big box retailers, and drive-thru ATMs,” reads a confidential Secret Service alert sent to multiple financial institutions and obtained by KrebsOnSecurity. “During previous attacks, fraudsters dressed as ATM technicians and attached a laptop computer with a mirror image of the ATMs operating system along with a mobile device to the targeted ATM.”

Reached for comment, Diebold shared an alert it sent to customers Friday warning of potential jackpotting attacks in the United States. Diebold’s alert confirms the attacks so far appear to be targeting front-loaded Opteva cash machines.

“As in Mexico last year, the attack mode involves a series of different steps to overcome security mechanism and the authorization process for setting the communication with the [cash] dispenser,” the Diebold security alert reads. A copy of the entire Diebold alert, complete with advice on how to mitigate these attacks, is available here (PDF).

The Secret Service alert explains that the attackers typically use an endoscope — a slender, flexible instrument traditionally used in medicine to give physicians a look inside the human body — to locate the internal portion of the cash machine where they can attach a cord that allows them to sync their laptop with the ATM’s computer.

An endoscope made to work in tandem with a mobile device. Source: gadgetsforgeeks.com.au

“Once this is complete, the ATM is controlled by the fraudsters and the ATM will appear Out of Service to potential customers,” reads the confidential Secret Service alert.

At this point, the crook(s) installing the malware will contact co-conspirators who can remotely control the ATMs and force the machines to dispense cash.

“In previous Ploutus.D attacks, the ATM continuously dispensed at a rate of 40 bills every 23 seconds,” the alert continues. Once the dispense cycle starts, the only way to stop it is to press cancel on the keypad. Otherwise, the machine is completely emptied of cash, according to the alert.

An 2017 analysis of Ploutus.D by security firm FireEye called it “one of the most advanced ATM malware families we’ve seen in the last few years.”

“Discovered for the first time in Mexico back in 2013, Ploutus enabled criminals to empty ATMs using either an external keyboard attached to the machine or via SMS message, a technique that had never been seen before,” FireEye’s Daniel Regalado wrote.

According to FireEye, the Ploutus attacks seen so far require thieves to somehow gain physical access to an ATM — either by picking its locks, using a stolen master key or otherwise removing or destroying part of the machine.

Regalado says the crime gangs typically responsible for these attacks deploy “money mules” to conduct the attacks and siphon cash from ATMs. The term refers to low-level operators within a criminal organization who are assigned high-risk jobs, such as installing ATM skimmers and otherwise physically tampering with cash machines.

“From there, the attackers can attach a physical keyboard to connect to the machine, and [use] an activation code provided by the boss in charge of the operation in order to dispense money from the ATM,” he wrote. “Once deployed to an ATM, Ploutus makes it possible for criminals to obtain thousands of dollars in minutes. While there are some risks of the money mule being caught by cameras, the speed in which the operation is carried out minimizes the mule’s risk.”

Indeed, the Secret Service memo shared by my source says the cash out crew/money mules typically take the dispensed cash and place it in a large bag. After the cash is taken from the ATM and the mule leaves, the phony technician(s) return to the site and remove their equipment from the compromised ATM.

“The last thing the fraudsters do before leaving the site is to plug the Ethernet cable back in,” the alert notes.

FireEye said all of the samples of Ploutus.D it examined targeted Diebold ATMs, but it warned that small changes to the malware’s code could enable it to be used against 40 different ATM vendors in 80 countries.

The Secret Service alert says ATMs still running on Windows XP are particularly vulnerable, and it urged ATM operators to update to a version of Windows 7 to defeat this specific type of attack.

This is a quickly developing story and may be updated multiple times over the next few days as more information becomes available.