Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg has raised eyebrows with a string of apparent attempts to woo Chinese authorities, from giving speeches in Chinese and jogging through Beijing smog, to leaving a Xi Jinping book on his desk while hosting former cyberczar Lu Wei, and even asking Xi to name his daughter. In March, a leaked propaganda directive calling for steps against “malicious commentary” on these efforts prompted speculation that Beijing might prove more receptive than many had supposed. So did internet regulator Ren Xianliang’s recent reiteration of the longstanding official position that “as long as they respect China’s laws, don’t harm the interests of the country, and don’t harm the interests of consumers, we welcome [Facebook and Google] to enter China.” On Tuesday, The New York Times’ Mike Isaac reported that the company has taken concrete steps towards satisfying these requirements, with the development of experimental censorship tools that might be wielded by a Chinese partner company.

[… T]he project illustrates the extent to which Facebook may be willing to compromise one of its core mission statements, “to make the world more open and connected,” to gain access to a market of 1.4 billion Chinese people. Even as Facebook faces pressure to continue growing — Mr. Zuckerberg has often asked where the company’s next billion users will come from — China has been cordoned off to the social network since 2009 because of the government’s strict rules around censorship of user content.

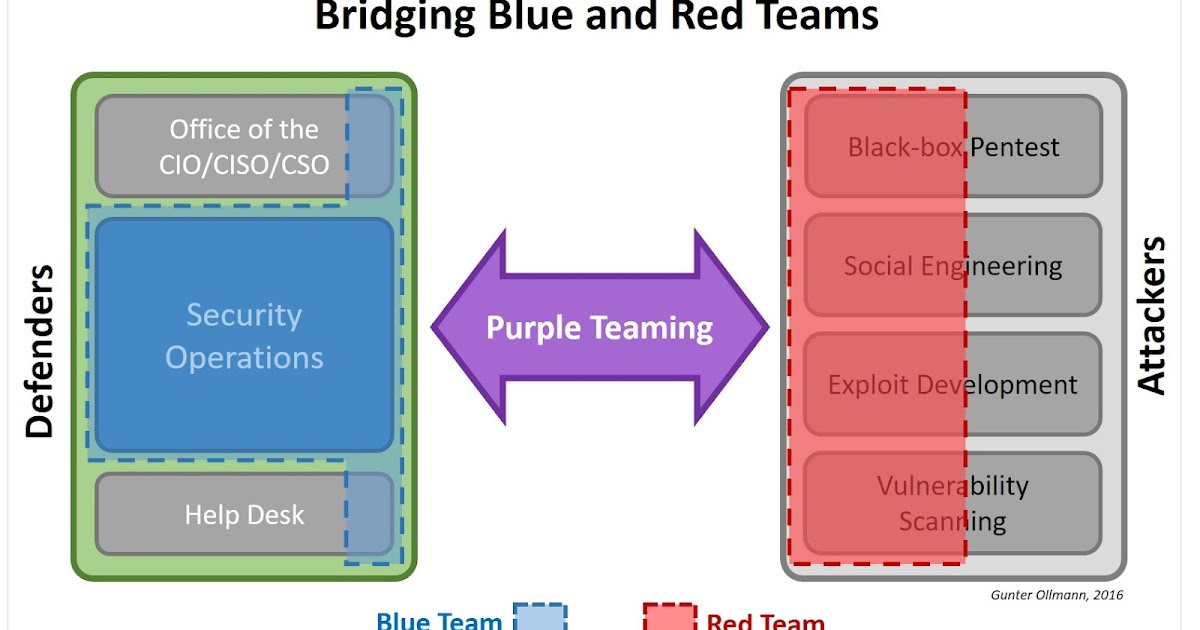

The suppression software has been contentious within Facebook, which is separately grappling with what should or should not be shown to its users after the American presidential election’s unexpected outcome spurred questions over fake news on the social network. Several employees who were working on the project have left Facebook after expressing misgivings about it, according to the current and former employees.

[… S]ome officials responsible for China’s tech policy have been willing to entertain the idea of Facebook’s operating in the country. It would legitimize China’s strict style of internet governance, and if done according to official standards, would enable easy tracking of political opinions deemed problematic. Even so, resistance remains at the top levels of Chinese leadership. [Source]

Bloomberg’s Sarah Frier similarly stressed that there seems to be no immediate prospect of Facebook’s entry into China:

Chief Executive Officer Mark Zuckerberg visits China frequently, and yet the company is no closer to putting employees in a downtown Beijing office it leased in 2014, according to a person familiar with the matter. The company hasn’t been able to get a license to put workers there, even though they would be selling ads shown outside the country, not running a domestic social network, the person said. The ad sales work is currently done in Hong Kong. The person asked not to be identified discussing private matters.

[…] China and Facebook aren’t engaged in ongoing talks about the conditions of a return, according to a separate person familiar with the matter who asked not to be identified as the matter is private. The ability to censor content would be a precondition, not the deciding factor, in any entry to the Chinese market, the person said. [Source]

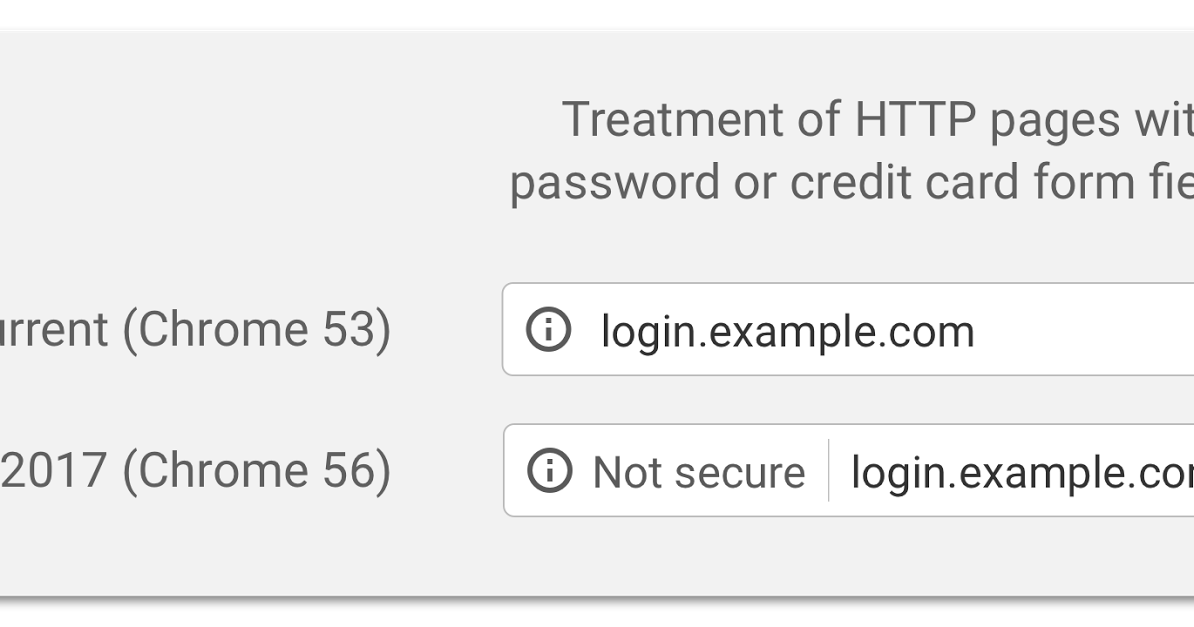

The current climate in China is hardly welcoming for foreign firms, particularly following the recent passage of a draconian new cybersecurity law which mandates self-censorship, unspecified “technical support” to authorities, security reviews, and local storage of user data. Cartoonist Rebel Pepper summed this situation up last week with a skeptical take on the third “World Internet Conference” held in Wuzhen:

The banner reads “World Disinternet Conference,” with bulian (不联), meaning “disconnected,” replacing hulian (互联), or “interconnected,” in the Chinese term for “internet,” hulianwang (互联网). Read more from CDT on the three World Internet Conferences China has hosted, including a round-up on this year’s with translation from a Xinhua commentary proclaiming Xi Jinping an “internet sage.”

CDT Chinese has compiled a few reactions to the New York Times report from Sina Weibo. Some users mocked Facebook’s supplications to the “Imperial Court”:

Jianchang’anbujianchang’an (@见长安不见长安): Cutting off your balls before entering the Imperial Palace?

Luyoudahongren (@旅游大红人): Hmm, developing a castrated magical weapon to present to the emperor, this palace eunuch’s wishes are very sincere

Guliquan (@贾利权): Facebook castrates itself, seeking entry to the Imperial Palace. [Chinese]

Others questioned the need for a limited Facebook in China, and its chances of ever getting there:

Guandengwuyanzu (@关灯吴彦祖): What would this actually achieve? So, we can access the same site as people abroad, but can only partially see what they post?

Xialuotewuhuishangdeguowang (@夏洛特舞会上的国王): So this is Facebook’s corporate value system? If so, besides feeling that there’s still no way they can enter the Chinese market, I’d also like to send them a “Grass Mud Horse” [“Fuck Your Mother”]!

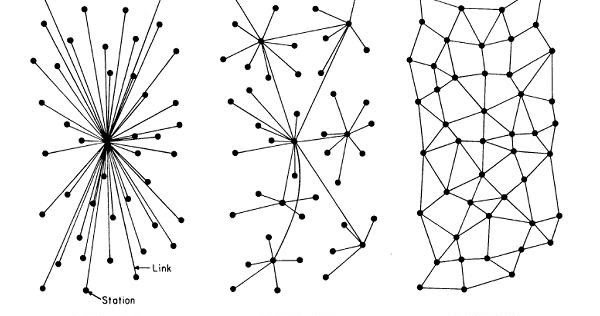

000000000oo (000000000哦哦): Making a Chinese version with restricted content, it’s still just a Local Area Network [not the real Internet]

Gongchandafahao (@共產大灋好): So what do we need you here for?

[The screenshot shows a “comments forbidden” notice on an article headlined “Xi Jinping: ‘We should welcome well-intentioned online comments’”]

Hulianwangdedashir (@互联网的大事儿): Better not to come at all …

Amiaoyu (@阿喵鱼): I want YouTube! I want Twitter! I don’t want to have to pay for a VPN every month ……

Zhengzaianfengdehuozhe (@正在安分的活着): We don’t need you, we need Twitter, we need YouTube, we need Google, we need Line, we need Instagram

Fengchezhuanbuting (@枫车转不停): I think there’s a way for Line to come in, but there’s already no room for Facebook

Liulianweihuabinggan (@榴莲威化饼干): There are a few apps that I hope never make it to the mainland … In the end, those who can all jump the Great Firewall. If it wasn’t there to block the others, they’d surge over and report everything back to the authorities

Fangtianyougou (@方田有沟): If Facebook hands the authority to examine and verify content to a Chinese partner firm, “China will be the biggest winner” [mocking a common formula for headlines in official media]. [Chinese]

Some users suggested rebranding, with one alluding to Xi Jinping’s call in February for state media to “take ‘Party’ as their surname”:

CD_Yim (@CD_Yim): If this is true, they should change the name to “book.” They’ve lost face.

Lihailewodege_ (@厉害了我的歌_): They should call it Partybook →_→

Liming_shouwang_zhe (@黎明守望者): Motherfucker, Facebook also has to take Party as its surname? [Chinese]

CDT cartoonist Badiucao proposed a new logo:

Another cartoon in a similar spirit has been deleted from Sina Weibo, according to the FreeWeibo monitoring site:

AdachushengzaiMeiguo (@Ada出生在美国): Facebook surnamed ‘Party,’ deletes posts at will, arbitrarily prohibits, perfectly loyal, please reconsider. [Chinese]

On Twitter, meanwhile, dozens of users scornfully contrasted Facebook’s apparent readiness to bow to Beijing with its reluctance to address the spread of fake news among users in America and elsewhere. By the U.S. election day earlier this month, fake news was substantially outperforming articles from mainstream news outlets on the platform. Founder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg initially protested that “the idea that fake news on Facebook … influenced the election … is a pretty crazy idea.” But criticism continued to mount, with The New York Times warning Zuckerberg not to let “liars and con artists hijack his platform.” He responded on Facebook that “we do not want to be arbiters of truth,” and that company would prefer “erring on the side of letting people share what they want whenever possible,” but said that the company was cautiously working to address the issue.

There has been no shortage of suggestions on ways to do this. According to some reports, Facebook already “absolutely [has] the tools to shut down fake news,” but has held off for fear of angering conservative users.

The U.S. election has also prompted renewed calls for information controls in China, where official campaigns against “rumor”—loosely and often politically defined—are well established. Officials reiterated the urgency of battling rumors and online extremism at the World Internet Conference last week, as Reuters’ Catherine Cadell reports:

Ren Xianling, the vice minister of China’s top internet authority, said on Thursday that the process was akin to “installing brakes on a car before driving on the road”.

Ren, number two at the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC), recommended using identification systems for netizens who post fake news and rumors, so they could “reward and punish” them.

The comments come as U.S. social networks Facebook Inc and Twitter Inc face a backlash over their role in the spread of false and malicious information generated by users, which some say helped sway the U.S. presidential election in favor of Republican candidate Donald Trump.

[…] Ma Huateng, the chairman and chief executive of Tencent Holdings Ltd, which oversees China’s most popular social networking app, WeChat, said Trump’s win sent an “alarm” to the global community about the dangers of fake news, a view echoed by other executives at the event. [Source]

An editorial in the state-run Global Times mocked the hypocrisy of the “Western media’s crusade against Facebook”:

[… M]edia platforms have the right to publish any information in the political field and cracking down on online rumors would confine freedom of speech. Isn’t this what the West advocates when it is at odds with emerging countries over Internet management? Why don’t they uphold those propositions any more?

China’s crackdown on online rumors a few years ago was harshly condemned by the West. It was a popular saying online that rumors could force truth to come out at that time, which morally affirmed the role of rumors. This argument was also hyped by Western media. Things changed really quickly, as the anxiety over Internet management has been transferred to the US.

[…] The Internet contains enormous energy, and the political risks that go along with it are unpredictable. China is on its way to strengthening Internet management, although how to manage it is another question. China is also right in demanding that US Internet companies, including Google and Facebook, abide by Chinese laws and be subject to supervision if they want to enter China market.

[…] Problems and conflicts caused by globalization and informationization have been unleashed in the Internet era, but the Western democratic system appears to be unable to address them. [Source]

But while some see the fake news pandemic as vindication of Chinese policy, others are unconvinced. At South China Morning Post last week, Jane Cai and Phoenix Kwong reported “Pony” Ma Huateng’s further statement at the WIC that “Tencent has always been strict in cracking down on fake news and we see it as very necessary.” But not all the Chinese executives in attendance shared his enthusiasm, they noted:

[…] Wu Wenhui, chief executive of China Reading, an online literature company, said regulators should not resort to extreme measures to tackle the problem unless it was absolutely necessary.

“The US incidents show the internet is more and more decentralised and people do not unanimously follow the opinions of experts,” Wu said.

“Regulators should respect the convenient platforms [of social media] for the public to express their opinions. They should also be open and be honest in communicating with the public,” he said. [Source]

Politico’s Jack Shafer, meanwhile, argued this week that “the cure for fake news is worse than the disease”:

[… T]he fake news moral panic looks to have legs, which means that somebody is likely to get hurt before it abates. Already, otherwise intelligent and calm observers are cheering plans set forth by Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg to censor users’ news feeds in a fashion that will eliminate fake news. Do we really want Facebook exercising this sort of top-down power to determine what is true or false? Wouldn’t we be revolted if one company owned all the newsstands and decided what was proper and improper reading fare?

Once established to crush fake news, the Facebook mechanism could be repurposed to crush other types of information that might cause moral panic. This cure for fake news is worse than the disease.

[…] Fake news is too important to be left to the Facebook remedy—Mark Zuckerberg is no arbiter of truth. First, we need to learn to live with a certain level of background fake news without overreacting. Next, we need to instruct readers on how to spot and avoid fake news, which many publications are already doing. A few years ago, Factcheck.org showed readers how to identify bogus email claims. Snopes does yeoman work in this area, as does BuzzFeed. Software wizards should be encouraged to create filters and tools, such as browser extensions, that sniff out bogusity. [Source]

Concerns about the concentration of information control powers in private hands have also arisen in China with, for example, a recent account suspension on Tencent’s WeChat platform over allegations that cheap roast duck came from diseased birds. From Oiwan Lam at Global Voices:

The WeChat account of Chinese news outlet News Breakfast was recently suspended for “spreading rumors.” News Breakfast has 400,000 subscribers in WeChat and is operated by East Day, a Shanghai city government-affiliated media outlet.

[…] The incident compelled Xu Shiping, the CEO of East Day, to write two open letters to Pony Ma Huateng, the chairman of WeChat’s parent company, Tencent, questioning the monopolized status of the Internet giant and its arbitrary power over online content and censorship. Like many other Chinese news outlets, News Breakfast publishes some stories only on WeChat, rather than publishing on its website and then promoting on the social media and content service.

[…] What is Tencent? It is an Internet company. It has a capital structure and cannot represent people’s interests […] In the past two years, Mr. Ma has been a guest of local governments which have provided corporate access to data which should be belong to the public. There is no evaluation of the capital value of such data access. […] Tencent’s monopoly is harmful to the state. Wait and see. Today it can exercise its unrestrained power on media outlets, tomorrow it will challenge state authority. […]

[…] If one day, all China’s media outlets are under the rule of Tencent, can we still have our “China Dream”? [Source]

Writing at Medium, ethnographer Christina Xu noted that false pro-Trump stories have proliferated in China, despite its strict information controls. Such stories, she suggested, are more a symptom than an underlying cause:

In an excellent series of tweets about rhetorical strategy, Bailey Poland wrote: “[Facts are] the support structure. It’s the foundation of reality on which an argument can be built, but it cannot be the whole argument.”

In China, that foundation of reality is eroded alongside trust in institutions previously tasked with upholding the truth. Contrary to popular sentiment in the US, Chinese readers don’t blindly trust the state-run media. Rather, they distrust it so much that they don’t trust any form of media, instead putting their faith in what their friends and family tell them. No institution is trusted enough to act as a definitive fact-checker, and so it’s easy for misinformation to proliferate unchecked.

This has been China’s story for decades. In 2016, it is starting to be the US’ story as well.

Propaganda that is blatant and issued from the top is easy to spot and refute; here in China, it’s literally printed on red banners your eyes learn to skip past. The spread of small falsehoods and uncertainty is murkier, more organic, and much harder to undo. The distortions of reality come in layers, each more surreal than the last. Fighting it requires more than just pointing out the facts; it requires restoring faith in a shared understanding of the truth. This is the lesson Americans need to learn, and fast. [Source]

Inside the Great Firewall? Download the CDT Browser Extension to access CDT from China without a VPN.